Feb 242011

By Susan Miron.

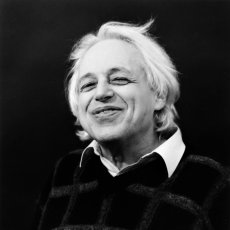

David Hoose, Music Director of the Cantata Singers and Ensemble since 1984, is the man in charge of marshaling the musical and spiritual resources for the performances, which take place on March 18th at 8 p.m. and March 20th at 3 p.m. at Jordan Hall, Boston, MA. The Arts Fuse’s classical critic spoke to him about the wonders, challenges, terror, and tenderness of Bach and his music.

ArtsFuse: Was there a moment in your life when this love of Bach hit you?

David Hoose: Well, there was that moment in sophomore music theory at Oberlin when the teacher played a recording (Karl Richter?) of the Magnificat, and my hair stood on end at the “Omnes! Omnes!” interruption of the wistful soprano and oboe d’amore duet. Wow! The Bach Magnificat, so succinct, brilliant, full of character, and bold in its emotion, speaks very easily to someone that age. So that’s probably when I began to see Bach as a living composer.

ArtsFuse: As a horn player, did you find this passion in works involving playing the horn, or was it though something you heard? At what age did this happen? Do you hold a special place in your heart for Quoniam tu solus sanctus (the horn solo in the B minor Mass)?

DH: Bach capitalized on the horn’s sound to evoke the regal. Since that’s a character not often needed, the number of works that give the horn independent parts is small—the First Brandenburg, one of the six cantatas in the Christmas Oratorio, the F major Lutheran Mass, only about a dozen cantatas and the B minor Mass. All in all, not very many times. But when it does appear, the horn always plays a crucial role. In the B minor, the horn (along with the two bassoons and other earthy instruments) flips the switch to launch the “Cum santo spiritu,” and what could be more exciting—to hear or play? I have to say that, even after so many years away from the horn, I’m still not sure how much of my excitement is musical and how much of it is empathy for the hornist who must sit silently for 45 minutes before committing fearlessly to such an exalted exclamation!

Arts Fuse: When did you first hear/play/conduct the B minor Mass? What was your initial reaction?

DH: I probably heard it first as an undergrad at Oberlin—it’s interesting how little music I knew before I went to college—and I’m not sure what I thought. Years later, in Boston, I played the Quoniam many times—one year over a dozen times—and it was always thrilling and, well, terrifying. Then, when I began to study the Mass to conduct it with Cantata Singers (in 1988), it became clear that I knew the first half rather well, but the second half (after the horn player might have gone home) seemed rather vague!

Over the years and through four or five sets of performances that I’ve conducted, this luminous testament of a rich musical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual life has become both more tangible and more mysterious. Like much of Bach’s music, the Mass in B minor knows no bounds, and that’s probably what captures all of us.

Arts Fuse: What did this piece mean to Ralph Vaughan Williams? Did he love Bach in general, and was that a lifetime love or something that happened after his deep acquaintance with Handel? What other composers did Vaughan Williams hold dear?

DH: That RVW conducted the Saint Matthew Passion 22 times (the last time only shortly before he died) and the B minor Mass nearly as many times, shows the reverence he had for this music. Wanting the communication unimpeded by the Latin or German, he lovingly prepared singing English translations of both works that he always used in performance. Though RVW probably didn’t know very many of the cantatas, the Mass and St. Matthew, along with a handful of other works, always played a guiding force in RVW’s performing and musical life. For him, too, Bach was a living composer.

Like most composers, RVW held strong opinions about others’ music. Just read his incendiary prose about some of them! Though he had little patience for Schoenberg or even Stravinsky, and he didn’t even seem to appreciate Elgar, his tastes were generous. And for many lesser composers—Parry and Stanford (both were his teachers)—and for his closest friend, Holst, his heart opened. And how many of us would go to study with someone 10 years our junior, as RVW did with Maurice Ravel? That showed a remarkable openness—and courage.

Arts Fuse: Do you think the Bach choral works and chamber works like the Brandenberg Concerti somehow reach many people deeper than say, the many great works for keyboard, cello, and violin? (This is perhaps a dumb question, but one to ponder).

DH: Actually, a fabulous question, though not solvable in a couple of sentences. But, briefly, the greatest composers’ music often display two attitudes: a public face and a private face, though one never to the exclusion of the other. Haydn’s intimate string quartets delight in intricacies, but their invention also reaches up to their large designs. And the outgoing symphonies, richest in their amazing large shapes, are full of delicious details.

We hear the same duality in Bach’s music but less than you might expect. The B minor Mass and the Matthew Passion concede nothing to their being public works, and any movement from the Mass embraces as much, if not more, detail than the cantata movement from which it derives. Paradoxically, it’s often the overtly religious works that touch the broadest range of people, shooting right past everyone’s resistance, whatever they may be, finding everyone’s openings, wherever they are, and filling everyone with amazed joy.

As for the popularity of the Brandenburg Concerti (and the four orchestra suites), I really don’t know. Maybe listeners are just happy to find music that, on the one hand, is public (lots of musicians) and, on the other, doesn’t speak in the unswerving evangelical voice of the passions, cantatas, and masses. But it’s all an illusion since the one thing that’s common to all of Bach’s music is his unswerving spiritual belief. It’s odd: that voice is inescapable, and yet the music makes room for absolutely everyone.

Ms. Miron elected not to describe the power of expression, musically communicative or otherwise, of the fine, subtle 1845 Pleyel salon grand lent to the Symposium by Patricia and Michael Frederick, other than to label its unfamiliar sound as “odd”. It is certainly not unusual for modern performers and reviewers not to have encountered or to have become curious about the pianos (or winds, strings, organs, brass, tympani, etc.) whose technical and sonic characters paved the way for the polished and, I must say, rather bland timbral palette required of most instruments today. However, I am sorry that, in her otherwise exemplary review, she did not feel that the special opportunity of hearing an authentic and visceral voice from Chopin’s own era and artistic milieu merited a small evaluative remark or two. A puzzlingly missed opportunity!

This particular salon grand, which I have delighted in recording a number of times in excellent concert conditions, immediately brings to mind those famous hallmarks of “the Pleyel sound” Chopin took care to jot down for the enlightenment of friends, and therefore for the eyes of discerning posterity. The original construction and Michael Frederick’s curatorially responsible voicing (in the course of a notably non-invasive restoration) of this modest-sized instrument result in detailed, gently veiled, and quite sweet tonal production. Not every pianist can make full musical sense of the particular keyboard scale and different key dip, pedaling sensitivity, and una corda use that this sort of just-pre-modern piano requires. Roberto Poli evidently brings flexibility and insatiable curiosity to bear when approaching any instrument, even a 160-year-old transitional Parisian piano by one of the celebrated makers of Chopin’s day.

Perhaps the New York Steinway, the de rigeur standard of our day, is the measuring staff by which, by default, all we hear is to be judged. How sad, though, not to seize and relish these precious, seldom-occuring opportunities for broadening, even deepening, our listening palette.

(Chamber music sessions this winter, in which Andrew Willis’s lovely 1845 Pleyel figured, thoroughly convined me that the 1840 Pleyel in the Frederick Collection indeed produces exactly the right sound for music of the period, be the scores French, German, or elsewhat. Either instrument’s extraordinarily easily moulded dynamics and deft evocation of voicing make for astonishing, irresistible results in collaborative music making.)